Whistler’s Symphony in White:

Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler

Joanna Hiffernan played an essential role in Whistler’s early years as an artist.

From 1860 onwards, she served as his muse, model, lover and confidante. He painted, sketched, etched and drew her many times over his career – most notably in White Girl: Symphony in White, No. 1.

Despite this, Joanna Hiffernan’s name is little-known, even within the artworld. A recent show held at the Royal Academy in London (an institution that previously rejected this masterpiece of modern art) seeks to change this.

Inspired by this exhibition, today we’re shining a light on this influential woman and her work with James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

Before we take a look at Whistler’s most famous painted portraits, who exactly was “the white girl”?

Who was Joanna Hiffernan?

Baptized in Limerick, Ireland in 1839, little is known of Joanna’s early life. We do know that by 1843 however, her family joined thousands of impoverished Irish migrants in London. Fleeing the effects of successive crop failures and rural poverty, she spent much of her early years in the English capital city.

Whistler was also an immigrant in London. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, he undertook his early art education in Paris in 1855, moving to London shortly after.

The pair met in 1860, and commenced an artistic and romantic partnership that changed the course of modern art…

What inspired Whistler to paint Symphony in White?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini (c1850) is frequently cited as an early inspiration for Whistler. Depicting the moment of the Annunciation in stark realism, a red-haired Mary appears paralyzed with shock and fear in the presence of her angelic visitor. The angel hands Mary a sprig of White lilies, symbolizing her transition from chastity to pregnancy.

Another inspiration came from Frederic Watt’s striking Lady Dalrymple c1851. In this portrait, the woman wears a loose-fitting, simple dress whilst standing on the balcony of Little Holland House in Kensington.

Ultimately however, Whistler’s artistic inspirations lay in color, harmony and “art for art’s sake”.

Contemporary commentators accused Whistler of capitalizing on the runaway success of Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White novel. Whistler categorically denied these claims, however. He described the painting as simply representing “a girl in white, standing in front of a white curtain”.

Of course, another key inspiration for Symphony in White was Whistler’s infatuation with Joanna Hiffernan. Writing to the artist Henri Fantin-Latour, Whistler described how Hiffernan had “the most beautiful hair you have ever seen.” He spoke of her copper-toned locks as “Venetian as a dream.”

Whistler’s paintings of Joanna Hiffernan

In addition to Symphony in White, Whistler created several famous painted portraits of Joanna Hiffernan throughout his career.

After his move to London, Whistler initially lived at respectable Sloane Street. He subsequently moved East to the Docklands area of London. His friend George Du Maurier described Whistler “working in secret down in Rotherhithe” amidst the most “beastly set of cads and every possible annoyance”.

Despite his friend’s consternation, Whistler painted some of his best-known paintings here, including Wapping on Thames. The painting prominently features Hiffernan alongside the French artist Alphonse Lagos.

Painted between 1860 and 1864, critics were concerned by the lack of an identifiable moral and the low neckline of Hiffernan’s dress. Despite this, Dante Gabriel Rossetti described the work as “the noblest of all the pictures” Whistler had created.

Hiffernan also appeared in another East London painting, Battersea Reach (1862). Her red hair and white dress are just visible as a ghost-like presence on the riverside.

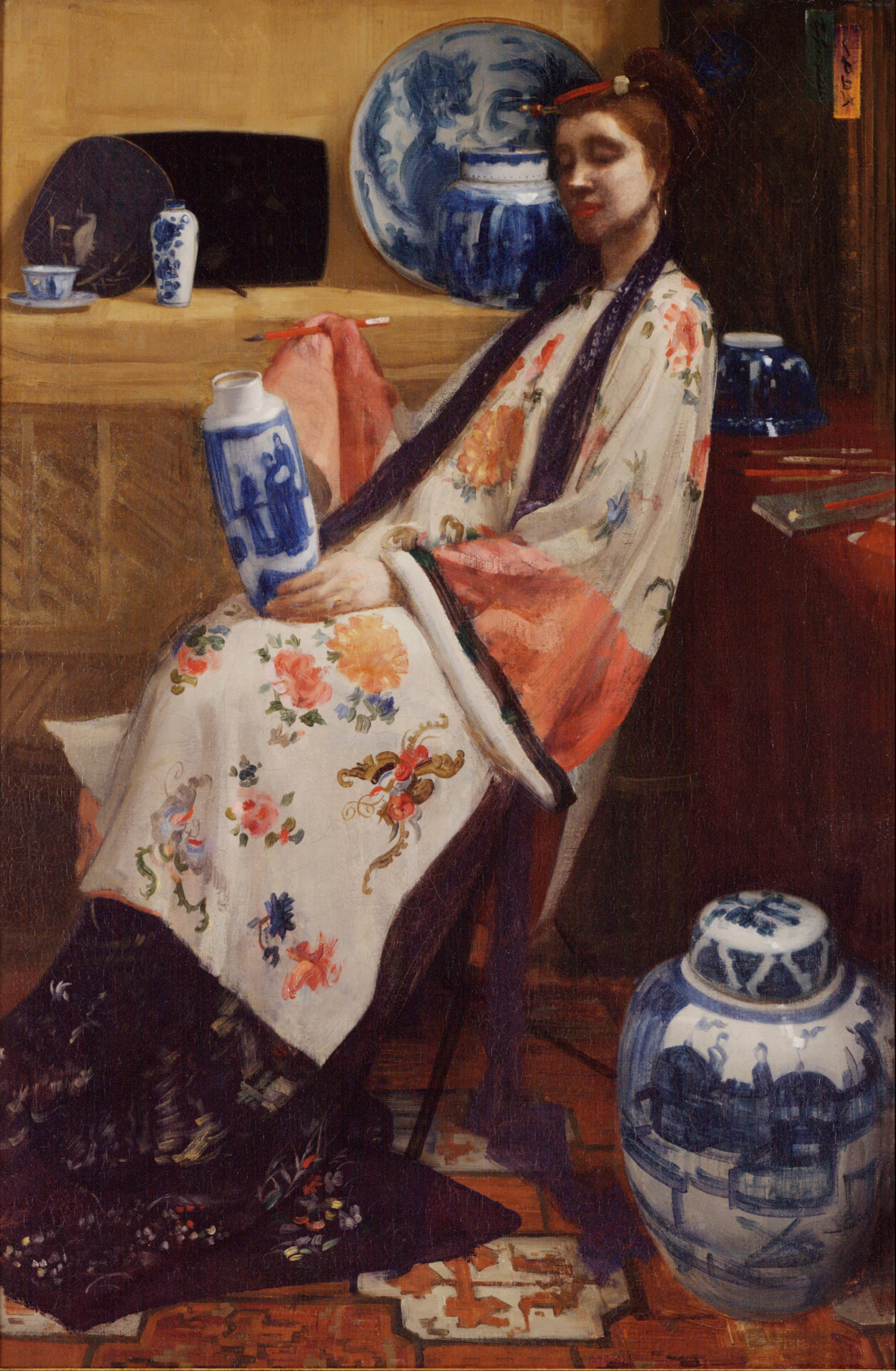

She also features in Whistler’s explorations into Japonisme, notably Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks and Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen (both painted in 1864).

As well as numerous drypoint etchings (revealing a touching insight into the couple’s intimate relationship), Hiffernan also appears in Whistler in his Studio (1865). In this composition highly reminiscent of Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas (1656), Whistler also stares out of the canvas.

From his studio, Whistler directly challenges the viewer’s gaze, raising issues of pictorial ownership and his own “possession” of Hiffernan.

Artistic possession and partnership

Whistler was deeply possessive of Hiffernan throughout their entire relationship. He refused to “lend” her to the painter Frederick Sandys, who requested Hiffernan for his portrait Gentle Spring (1865).

Ironically however, Sandys hired Emelie “Millie” Eyre Jones for the work (the second woman in Whistler’s later Symphony in White, No. 3). The two paintings hung side by side in direct competition at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1867.

The only other artist “allowed” to paint Hiffernan was Whistler’s friend Gustave Courbet. The two men (accompanied by Hiffernan) went on a memorable holiday to the Normandy Coast in 1865.

Here, Courbet described Hiffernan as a “superb redhead” and painted her portrait in Jo the Beautiful Irishwoman (1866). Courbet refused to ever sell the painting, instead painting three additional versions for sale.

Before his death in 1877, Courbet wrote to Whistler nostalgically recalling their trip with Hiffernan. He described how she “sang Irish songs” and “played the clown” to amuse the two men. Courbet opined she sang so well because she had the true “spirit and distinction of art”.

The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler

Originally titled “The White Girl”, Whistler’s Symphony in White, No. 1 is actually one of three paintings depicting Hiffernan in her iconic white dress.

The first Symphony in White (1861-3) was rejected by the highly traditional Royal Academy. Joanna described how “Millais thinks it splendid” however, saying it was “more like Titian” than anything he’d previously seen.

She added comically “Jim says for all that, the old chuffers [at the Royal Academy] may refuse it all together.” The painting was simply too abstract for art audiences more used to narrative works.

Later displayed at the 1863 Paris Salon des Refusés, one critic described the work as a Symphonie du Blanc. After this, Whistler changed the name.

The painting caused a great sensation (both for and against) in Paris, helped in no small measure by its display alongside Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe.

Variations on Whistler’s Symphony in White

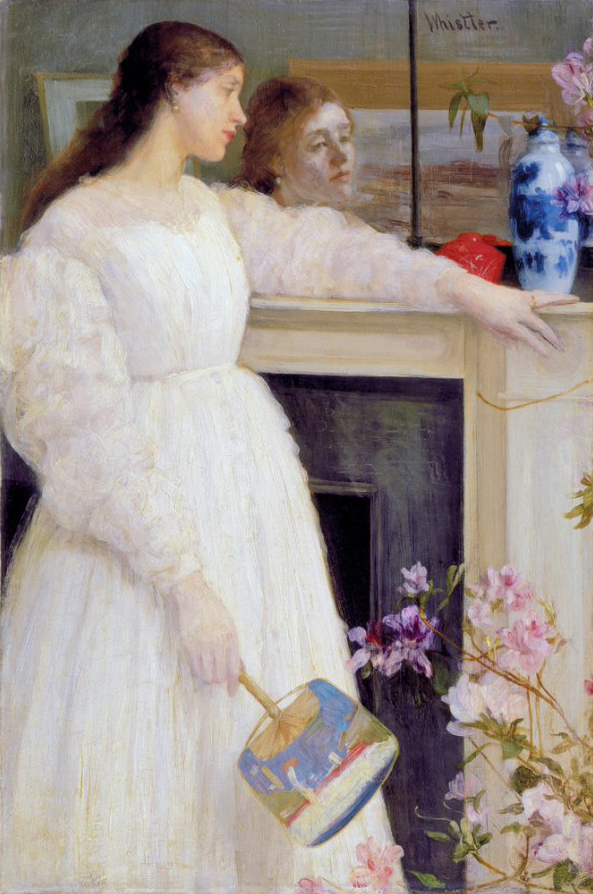

After the significant publicity of his Symphony in White, Whistler painted The Little White Girl, otherwise known as Symphony in White, No. 2. Here, Hiffernan wears a fine white muslin dress, standing in front of the fireplace at Whistler’s Chelsea home.

In the painting, Hiffernan’s fan features a woodcut by Hiroshige (The Bank of the Sumida River). The same Hiroshige print is also visible in Whistler’s Caprice in Purple and Gold.

The white and blue porcelain further references Whistler’s growing fascination with Japonisme. In a further intriguing detail, Hiffernan noticeably wears a wedding ring. She never married, however.

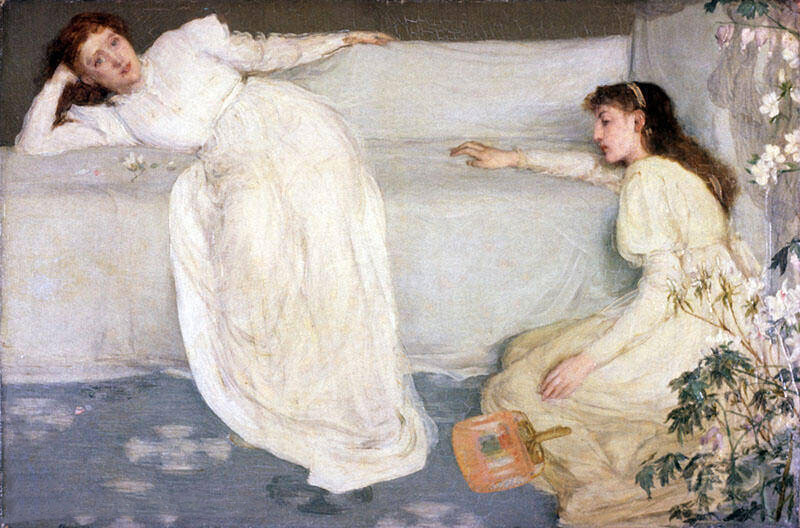

Completing the trio is Symphony in White, No. 3, painted between 1865 and 1867. Featuring Hiffernan alongside Emelie Jones (the model for Sandy’s Gentle Spring), Whistler was particularly proud of this painting. In a letter to Latour, he described the “very delicate gray background” and Jo wearing the same white dress as his earlier work.

Whistler also claimed Hiffernan’s figure was the “purest” he’d ever created. Other artists clearly agreed, with Edgar Degas sketching the painting at its 1867 exhibition in Paris.

Why is Whistler’s Symphony in White important?

Aside from being a true masterpiece in its own right, Whistler’s Symphony in White inspired many subsequent artists (especially during the American Gilded Age). Some of its many fans included the Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais, the Vienna Secessionist Gustav Klimt and the American painter Albert Herter.

Albert Herter’s Portrait of Bessie (1892) directly references Whistler with its white lilies and bearskin rug. The muted, almost abstracted color palette further speaks to Whistler’s groundbreaking exploration of white.

Whilst the woman in Millais’ A Somnambulist bears a striking resemblance to Hiffernan, the painting differs in its distinct narrative qualities. Referencing Bellini’s opera La Sonnambula (“The Sleepwalker”), it shows the female protagonist sleepwalking dangerously close to a cliff.

There are also uncanny similarities with Gustav Klimt. Klimt tackled the “woman in white” theme many times, notably in Portrait of Gertrude Loew (1902), Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904) and Portrait of a Lady in White (1917).

Just like Whistler, Klimt also had a flame-haired muse. He frequently painted the model known as “Red Hilda” throughout his career, most notably in Danaë and The Kiss.

Reproduction Gallery proudly boasts an unparalleled collection of James Abbott McNeill Whistler artworks. Browse our oil painting reproductions today and enjoy the beauty and delicacy of Whistler’s art on your walls.

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.