Dada Art Movement Oil Painting Reproductions

Find Dada Art Movement Oil Painting Replicas By Dada Artists

Dada Art Movement: A Brief Introduction

Dada art movement was formed in Zurich in response to the futility, death, and destruction of the First World War; it embraced nonsense, satire, and absurdity in art. How should a civilization and its art respond in light of the end of tens of millions of military personnel and civilians? This was the quest and question of the Dada artists.

In this brief introduction, you can learn more about this fascinating movement and its pioneering artists.

What was the Dada art movement?

A definition is notoriously elusive. However, this is part of the appeal of Dadaism. Originating during the early 20th century, Dada artists tried to destroy traditional values in art and society. They were responding to the First World War and the system of nationalism and militarism that facilitated the conflict.

Followers of Dadaism created an entirely new conception of art. In so doing, they replaced old ways of doing and seeing. Full of humor, satire, and fun, Dada art fundamentally changed European art. Dada artists are also associated with sculpture, poetry, and performance art.

The art movement was anti-war, politically leftist, and anti-bourgeois, believing the upper classes were the primary defenders of traditional art and society.

After the war, the movement quickly spread all over Europe. It boasted artistic groups in Paris, Cologne, Hanover, Berlin, and the Netherlands. Finally, Dada reached Japan and New York with artists such as Tomoyoshi Murayama, Man Ray, and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

The movement lasted until the mid-1920s when new avant-garde approaches such as Cubism and Surrealism took over.

What inspired Dadaism?

Revolted by the horrors of the First World War, Dada artists made art questioning everything about the society enabling such carnage. The poet Tristan Tzara described how it was not the beginning of art but the launch of disgust. For Dadaists, the war confirmed the corruption and nationalism of all politicians. They believed that changing repressive social values and cultural assumptions was necessary, and this inspired their art.

As a leading Dada artist, Jean Arp, once said, “While the guns rumbled in the distance,” we created art. He described how they “sang, painted, made collages, and wrote poems with all our might.”

Asked about the meaning of “Dada,” artists associated with the art movement provide several, often contradictory and humorous, definitions. These included Dada is… “anti-art,” “irony,” and even “Dada will kick you in the behind.” The word is a nonsense utterance.

Some stories relate the name arose through stabbing knives into a dictionary. Others argue it was an amalgamation of European languages, for instance, Russian for “yes, yes” or French for “hobby horse.” If there is a “real” original meaning, this remains unknown.

What was the Dada art movement known for?

The movement is primarily known for its humorous and irreverent art. There was no standard style or approach but merely to “destroy the hoaxes of reason” and discover an “unreasoned order.”

Dada paintings frequently critiqued modernity, referencing newspapers, films, advertisements, and the new machine age. Also known for using unorthodox materials, Dada art includes newspaper cuttings, glue, and photomontage.

This art movement further inspired later Surrealism and Conceptualism. Marcel Duchamp’s unique creations particularly influenced the development of European creativity. By fundamentally questioning “what art is,” he instigated new ways of approaching art and its societal role.

What are the three characteristics of Dada art?

The Dada art movement was never concerned with setting rules and regulations for how art should look. Consequently, Dadaism took many shapes and forms. Some artists like George Grosz created “representational” art with recognizable figures and objects. Other famous Dada artists, such as Sophie Taeuber Arp, Francis Picabia, and Theo von Doesburg, took a more abstract approach.

Whatever form the artworks took, however, they all deconstructed everyday experiences in a challenging and satirical manner. Some fundamental characteristics emerged in attempting to reconcile the silly with the destruction of creativity. This includes:

- Irreverence and Humor: A lack of respect for convention, authority, and rules. Dadaists were interested in the power of humor, demonstrating the lack of intrinsic value or superiority in anything.

- Assemblage: Marcel Duchamp is the most famous pioneer of ready-made assemblages (i.e., repurposing everyday objects as works of art). This often-bizarre method of creating art also characterized the work of Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Raoul Hausmann.

- Chance: was an essential characteristic of Dada art. Artists embraced randomness and accident as a method of escaping rational control. “Chance” was particularly prominent in the art of Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters, and Marcel Duchamp.

Who is Famous for Dada?

Many famous Dada artists exist, but the German poet and writer Hugo Ball was the movement’s founder.

In 1916, HugoBall founded a stylish avant-garde nightclub in Zurich. Deeply satirical and sarcastic, he named the institution Cabaret Voltaire. The club, and its raucous goings-on, became a focal point for the movement. It saw infamous performance pieces like Hugo Ball’s recital of the sound poem “Karawane.” This performance consisted of nonsensical syllables uttered in rhythmic, emotional patterns. Hugo Ball spoke while wearing a cardboard suit representing the inability of European leaders to solve disputes through diplomacy and rationality. In addition to Cabaret Voltaire, Ball instigated a magazine. The first of many Dada publications, he named it “Dada, Dada, Dada, Dada, Dada.”

Who were the leading Dada artists?

Given its broad geographic spread and lack of a formal constitution, no single set of Dada artists existed. Dadaism artists worked worldwide, inspired by the Dada movement and its overarching goals.

Here are seven artists, all influenced and inspired by Dadaism.

Alice Bailly

A Swiss avant-garde painter and close friend of Francis Picabia. Alice Bailly is known for her contributions to Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism and her participation in the movement.

Bailly’s paintings, such as Marvel at the van-Dongen Masked Ball juxtapose abstracted figures with vivid, swirling shapes. They embrace the sense of cultivated confusion and chaos, aiming at provoking violent reactions.

Francis Picabia

A French avant-garde painter and poet, Picabia worked across many artistic styles. He is associated with Cubism, Abstract Art, Dada, and Surrealism. His abstract art paintings are colorful and dynamic. As one of the early figures of Dada art in France and the United States, he started a Dada periodical titled 391.

Despite this, Francis Picabia broke away from the movement in 1919. Moving towards Surrealism, he denounced Dada formally in 1921 and published several scathing attacks in the final issues of his periodical 391.

George Grosz

George Grosz paintings often refer to the horrors of war and contemporary German society. He was a prominent member of Dada, German Expressionism, and the “New Objectivity” emerging during the Weimar Republic.

Indeed, Grosz co-founded the Berlin Dada movement. He used his satirical illustrations to attack bourgeois supporters of the new republic. These drawings also informed his painting The Pillars of Society, often featuring overweight people in business contrasting with wounded soldiers and prostitutes.

Max Ernst

As a German painter, sculptor, and poet, Max Ernst was an early pioneer of the Dada movement. He lacked formal artistic training but championed an efficient way of creating art. This led to the invention of “frottage,” a technique using pencil rubbings of objects as the basis of compositions.

Also inspired by surrealist approaches, Max Ernst paintings are often shocking in their irreverence. This is particularly noticeable in later paintings such as Young Virgin Spanking the Infant Jesus in Front of Three Witnesses.

Otto Dix

A German painter and printmaker, Otto Dix was particularly famed for his ruthless and harsh depictions of contemporary society and the brutality of war. These include portrayals of journalists, sex workers, art dealers, and lawyers.

Alongside George Grosz, he’s among the most influential New Objectivity artists. Influenced by Dada, Otto Dix often incorporates collages in his paintings. He exhibited at the first-ever “Dada Fair” in Berlin.

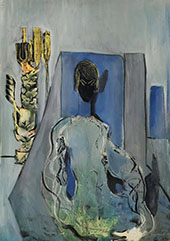

Sophie Taeuber Arp

Although better known as a Constructivist artist, Sophie Taeuber Arp was heavily influential in the movement and a co-signatory of the Zurich Dada Manifesto. Meeting Hans Arp in 1915, the two artists married soon after. They both associated with Dada and shaped its development.

Taeuber Arp’s sculpture Dada Head 1920 was revolutionary in using ordinary materials such as wood, wire, and beads. She also led Dada-inspired performances, often at the Cabaret Voltaire, as a puppeteer, dancer, and choreographer.

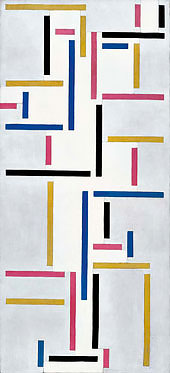

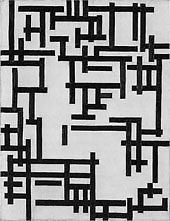

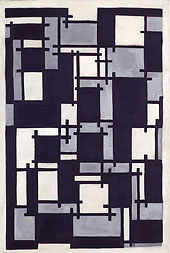

Theo van Doesburg

While famed as the founder of the De Stijl movement and Piet Mondrian, van Doesburg was also influenced by Dadaism. He maintained links with Dada art movement painters throughout his career and published the magazine Mécano under the name I.K. Bosnet. In true Dada fashion, the title links to the Dutch for “I am foolish.” Doesburg also published Dada poetry under the same pseudonym in the De Stijl journal.

Dada Oil Painting Reproductions

Discover the humor and irreverence of the Dada art movement oil paintings. Reproduction oil paintings are completed entirely by hand, and we offer paintings by some of the most famous 20th century artists.

Fine art reproductions are handpainted, and colorful paintings are available as oversized wall art.

Cannot Find What You Are Looking For?

Reproduction Gallery Information

Customer Service

(Send Us A Message)

Tel: (503) 937 2010

Fax: (503) 937 2011